My child is not listening… what can I do?

There is always a moment when you wish the child could listen better.

Before delving into ways to “make” children listen, there are two useful concepts that are crucial for adults to understand when helping children cultivate good regulation skills.

Self-regulation:

Some of you might have encountered the term “self-regulation” before when exploring children’s emotion management. Self-regulation originally refers to the ability to manage and monitor our cognition (metacognition) and neo-behavioural outcomes, checking the planning and outcome of our thinking and behaviour. Later, academics expanded the scope to include self-regulated learning, examining how cognitive, motivational, and volitional factors interact and play a role in building self-regulation. All of these share common concepts: the ability for self-awareness and the production of appropriate regulatory action. Therefore, we not only consider the children’s response but also their adaptability to predicted and unpredicted events in our lives. Shanker once suggested that self-regulation development comes after five domains of ability: biological, emotional, cognitive, social, and prosocial ability. An established self-regulation can be seen as the consequential outcome after all the baby steps of development in the five categories of skills with good cooperation between the skills.

Domain of Development

- The ability to maintain and change the level of arousal appropriately according to the external environment (tasks & situations).

- The ability to monitor and modify one’s emotions.

- The ability to attend and focus on tasks or external challenges.

- The ability to control one’s negative emotions.

- Resilience towards frustration and the ability to selectively engage in useful information that helps one deal with the situation.

- The ability to inhibit impulses and produce appropriate behavioural responses.

- The ability to read social cues and display socially appropriate behaviour.

The ability to appropriately monitor one’s behaviour and evaluate progress towards socially constructed goals.

- The development of empathy and values. The skills of thinking and planning, as well as the ability to learn and reflect.

When discussing strategies in regulation, there are mainly two directions: arousal or emotional-focused and thinking-focused. For children, due to the novelty of the idea of being aware of one’s emotion and behaviour, adults are required to be the “matured brain” for the children, assisting them in becoming aware of their emotions and thinking, and then coming up with strategies to enhance their performance throughout their daily activities.

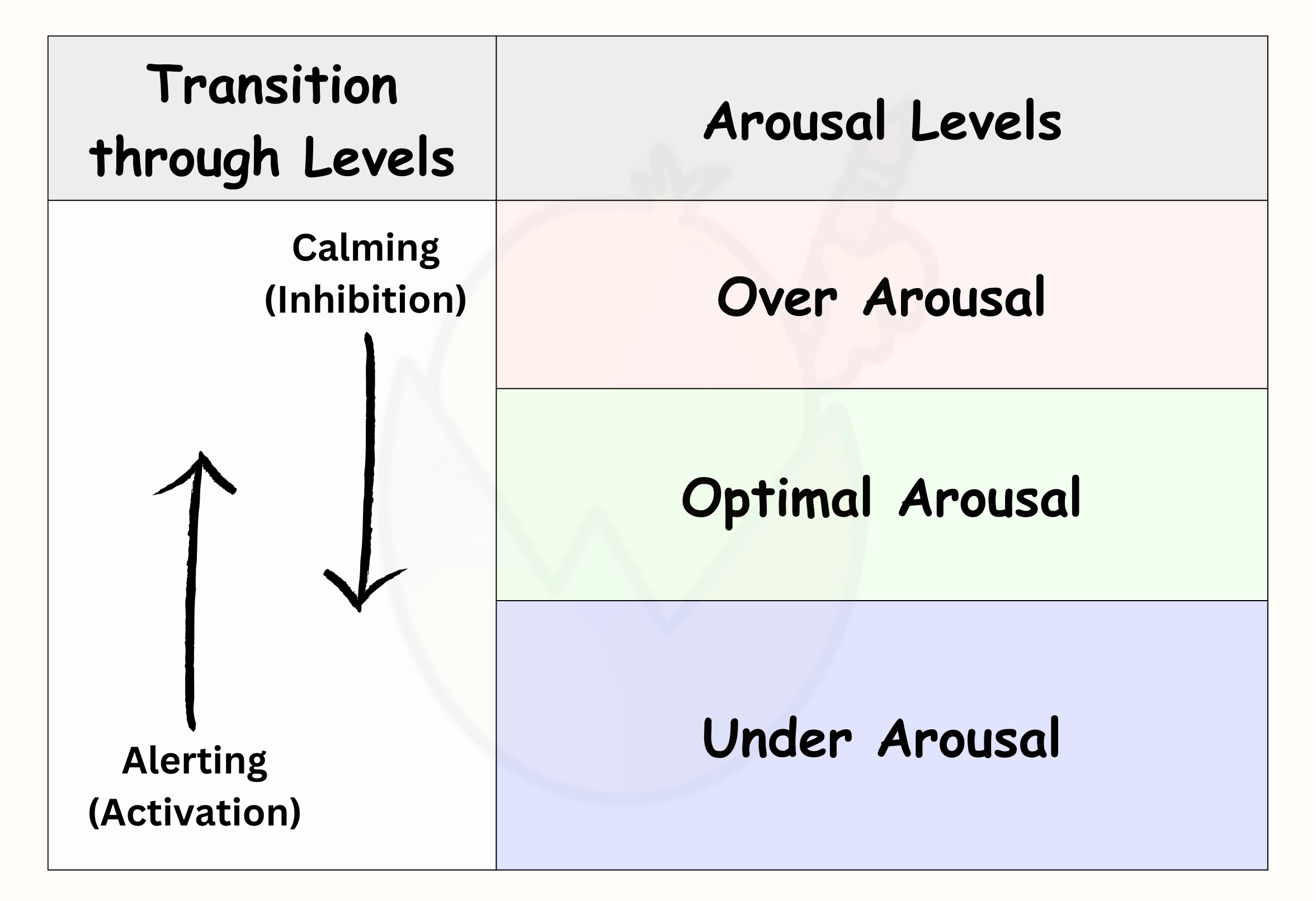

So What are the 3 Arousal Levels?

Once we have adequate self-regulation skills, we are in a better position to manage the arousal that aligns with the task and situation. There are a few ways to understand the idea of arousal. In general, arousal level refers to our alertness levels. There are usually three main stages of arousal levels.

Under Arousal:

When we are in the under-arousal stage, we usually find ourselves being lethargic and tired. Focusing becomes challenging when under-aroused. For children, you might find them in this stage easily distracted, tired, and taking more time or input to respond to stimuli from the environment.

Optimal Arousal:

This stage is the time when we find ourselves focused and concentrated on performing tasks. Our thinking and regulation skills work best during this stage. Children are the same. They sense, think, regulate, and perform the best while in this stage.

Over Arousal:

While in the over-arousal stage, we may find ourselves more excited. Imagine the mental state of athletes participating in a competition. When we get more excited with stimuli from the environment, we experience more excitement, which might result in being too excited. In children, we often find those who are over-aroused being more agitated and starting to get more disorganized and busier with movements while sitting on a chair. Children at the further extent of the over-aroused state might find active listening, regulating, and following instructions difficult.

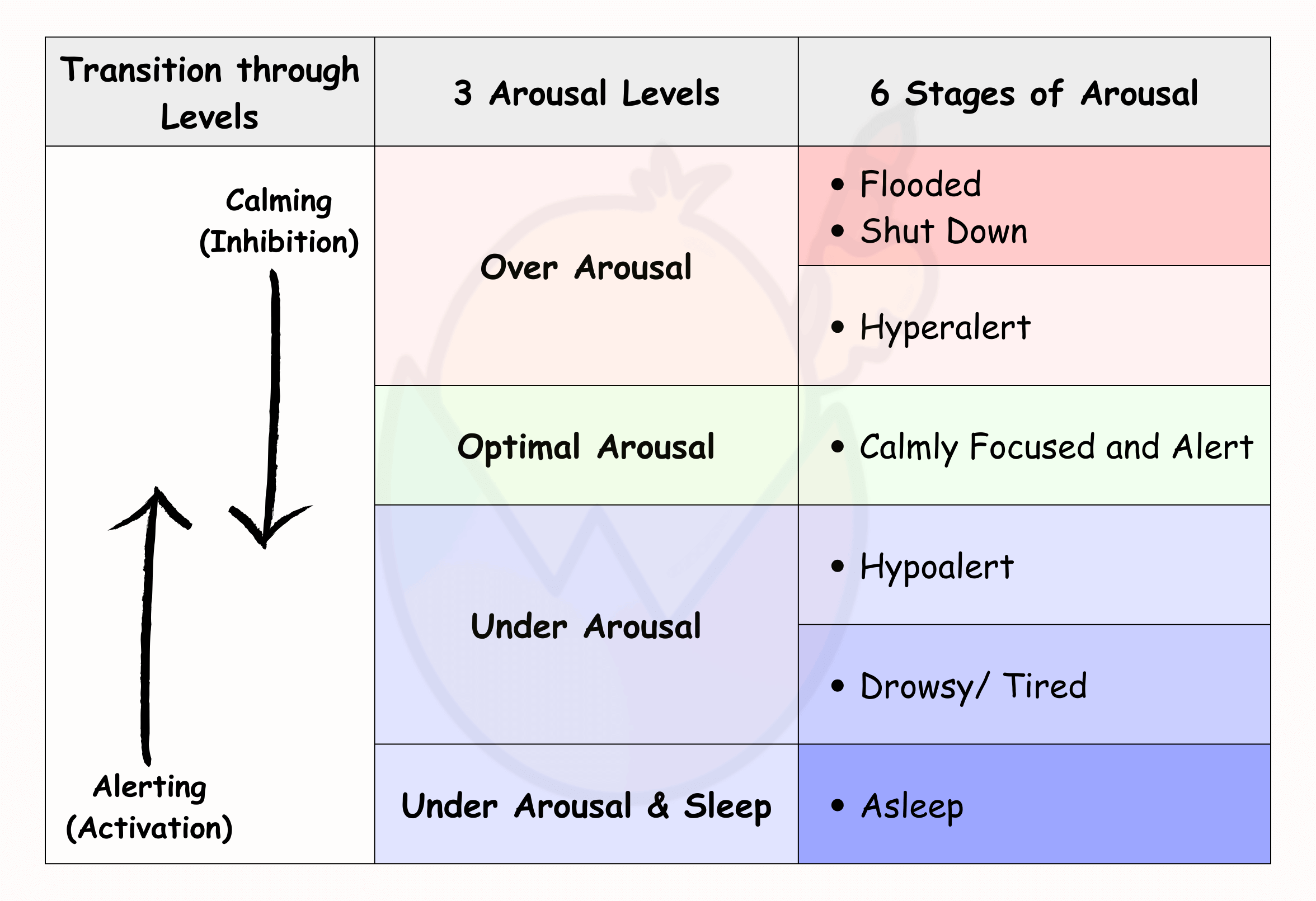

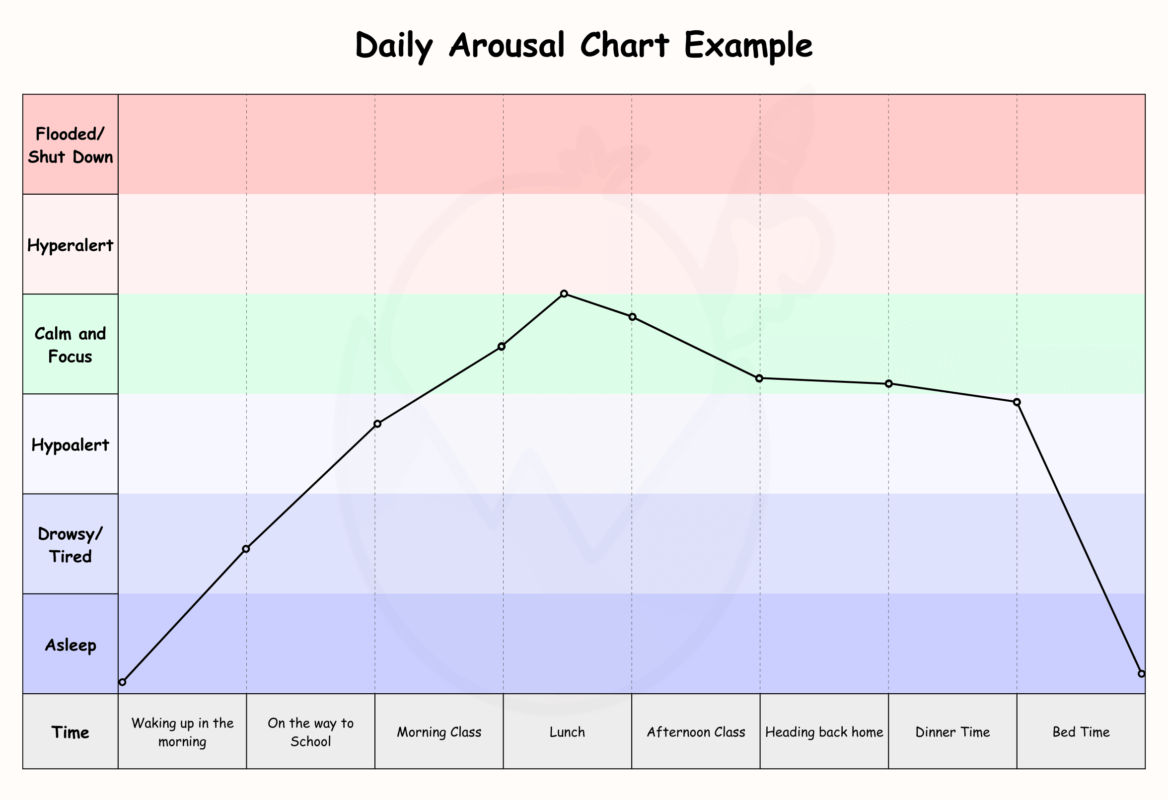

The 6 Stages:

Dr. Stuart Shanker, the founder and science director of The MEHRIT Centre and Self-Reg Global Inc, suggests that there are six main stages of arousal: asleep, drowsy, hypoalert, calmly focused and alert, hyperalert, and flooded. Generally, human beings transition through these stages based on their energy levels and the demands of different situations. Here, energy is likened to the fuel utilised during various activities.

In certain situations, children might expend more “energy” dealing with negative emotions, stress, or anxiety. When in such emotional states, children may face obstacles by being overly alert, triggering the flight-or-fight response to a specific situation. This can deplete children’s energy, reducing the likelihood of effective learning and establishing appropriate responses. As children develop a more mature self-awareness and response, they become better equipped to return to a calm & alert state, reacting attentively and promptly to external challenges. Achieving this requires practice over time and exposure to various social events.

Good Regulation Skills Takes Time:

Different children exhibit varying styles of response to social events or challenges. As adults, it is crucial to recognise each child’s unique response style and provide guidance to help them develop better self-regulation and resilience. Studies show that responsive parenting/teaching and a safe, secure environment positively contribute to children’s learning. It’s important to refrain from blaming behaviour and correcting it with a stern attitude. Instead, the focus should be on understanding the reasons behind the behaviour and finding ways to assist individuals in building better self-regulation skills.

Here are some smart ways to help children understand and visualise their arousal levels and improve their regulation skills.

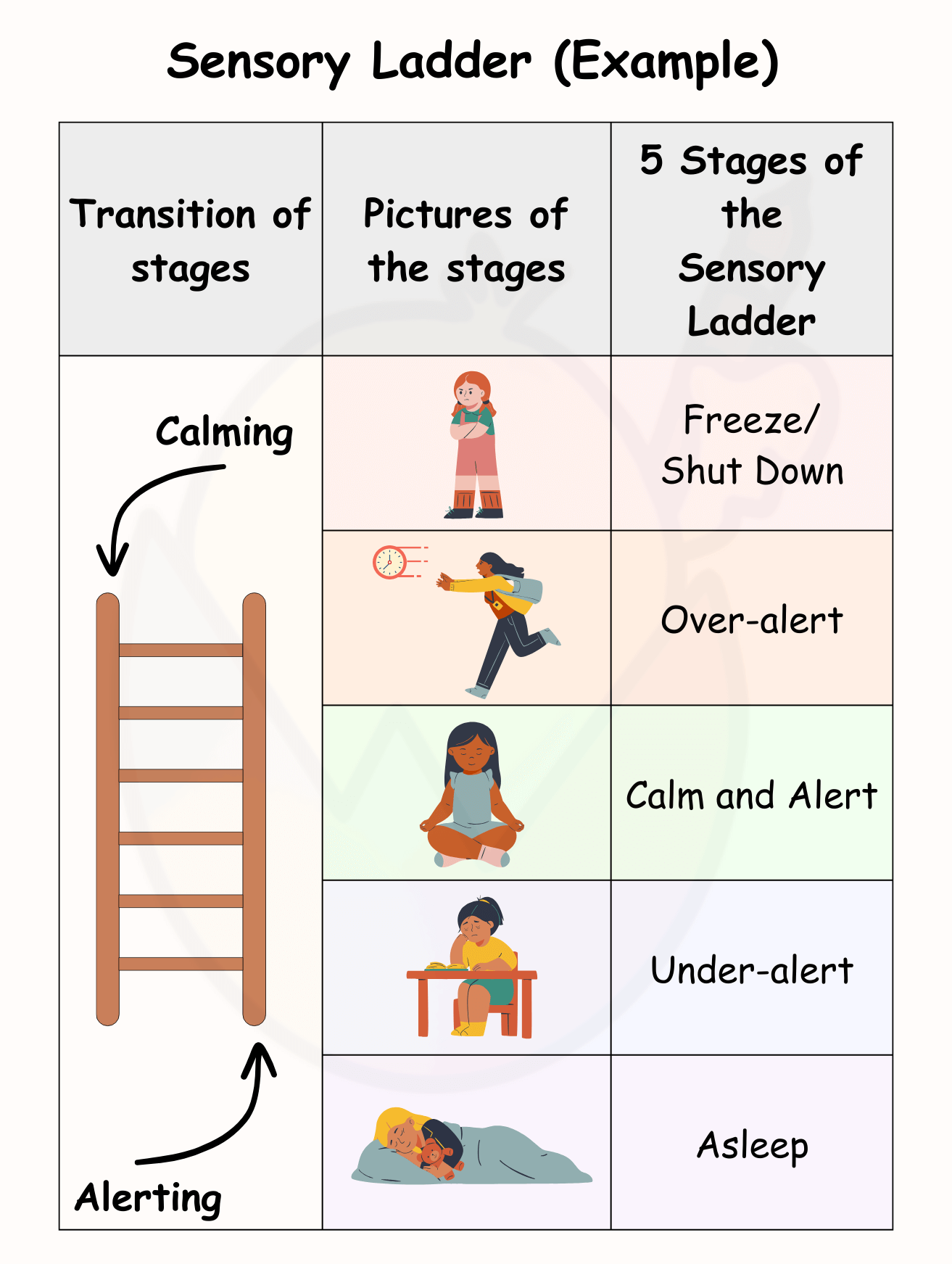

Sensory Ladder:

The Sensory Ladder is a tool designed by Kath Smith, an Occupational Therapist. It serves as a helpful tool to assist children in visualising their arousal levels and reminding them of useful responses to manage social situations. Each child can create their own ladder, comprising five main levels: Sleep State, Under-alert, Calm and Alert, Over-Alert, and Shut Down. It can be beneficial for a child to associate each level with an animal or visualise themselves in these different stages to enhance self-remembrance. Adults, whether parents or professionals, can explain arousal levels using examples (or wording) specific to the child they are working with.

Once the child gains a better grasp of the idea of these levels, both can collaborate on developing practical strategies to move up (activate) or down (calm down) the ladder. Children can identify and make note of activities that help them become more alert or calm and focused, then integrate them with the ladder.

Upon completing their own Sensory Ladder, children can keep it with them at home and in school to assist in coping with social situations. This can serve as a valuable starting point for collaboration between teaching professionals, healthcare professionals, and families.

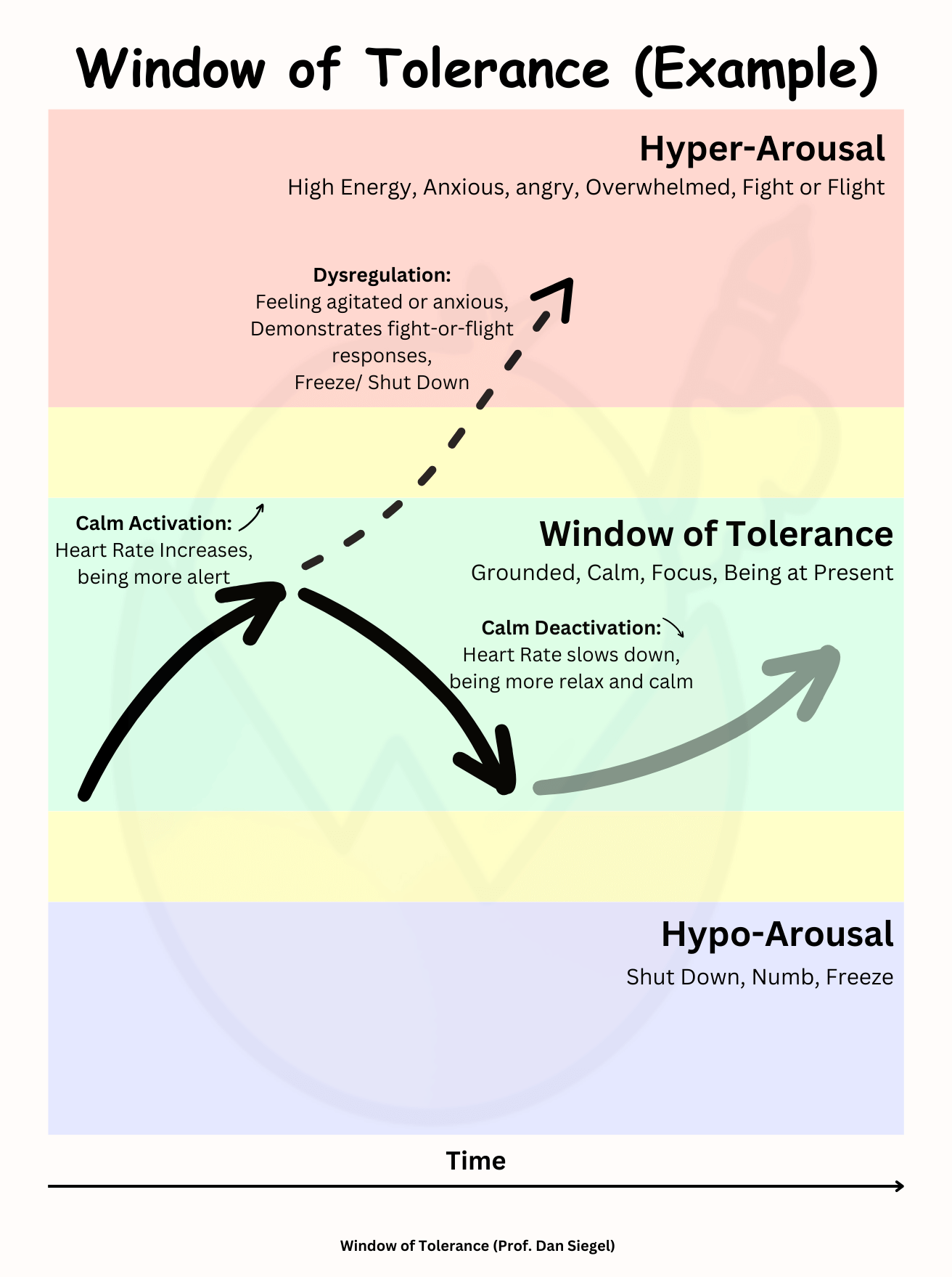

Window of Tolerance:

The “Window of Tolerance” was established by Dan Siegel, a Clinical Professor of Psychiatry. Originally designed to assist people in developing good mental health and wellbeing, it helps individuals recognize their arousal levels in response to various social events. The concept comprises three main stages: Hyper-arousal, Window of Tolerance, and Hypo-arousal. Dysregulation may occur when an individual deviates outside of their window of tolerance. It is common for children to feel agitated or anxious during the dysregulation stage. This could be the time when the flight-or-fight or freeze response manifests in response to external challenges.

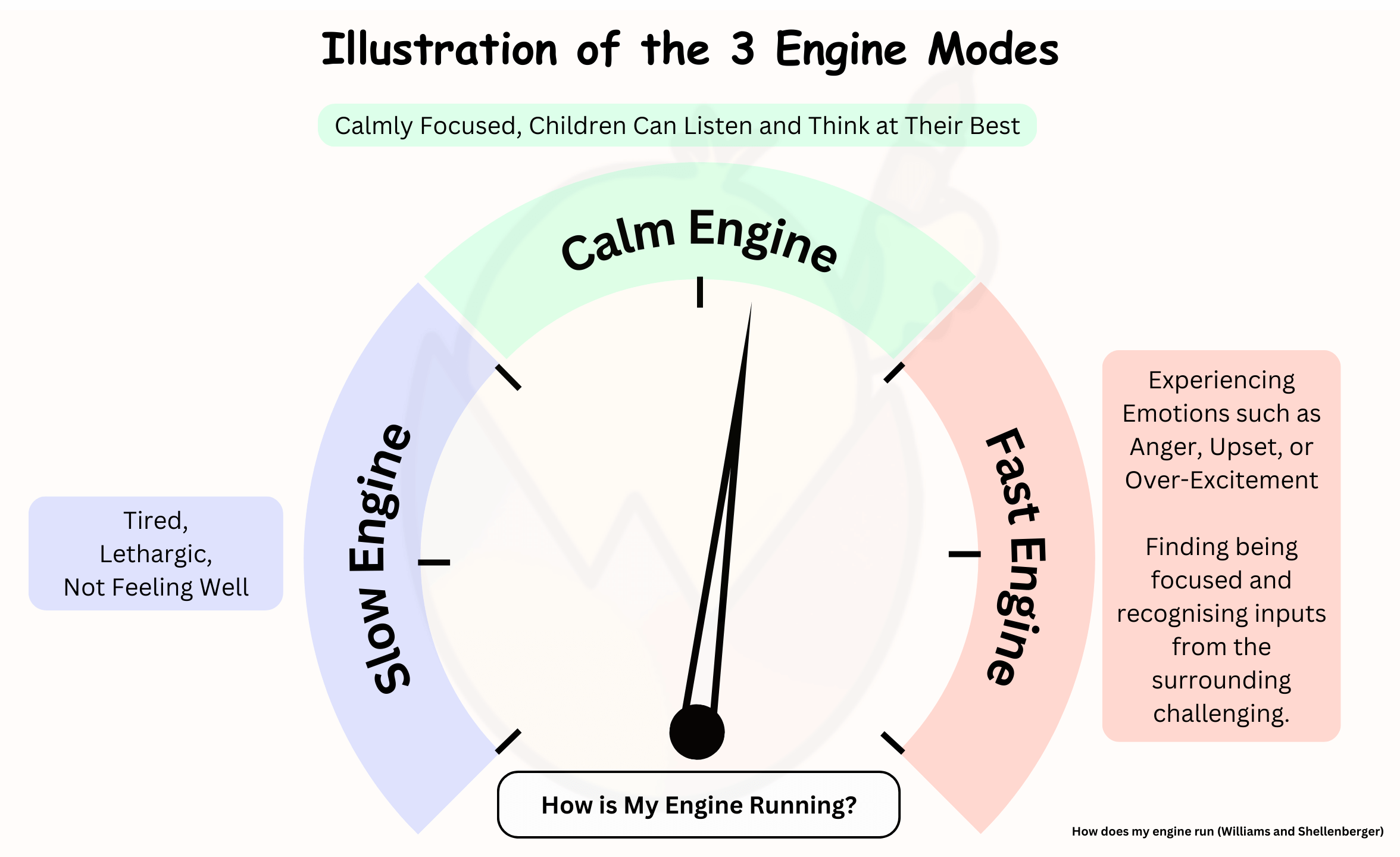

How Does your Engine Run:

“How Does Your Engine Run” was designed by Williams & Shellenberger, two Occupational Therapists who proposed the pyramid of learning. This framework helps reflect children’s arousal levels in three main states: low, just right, and high.

The “fast engine” illustrates the over-alert arousal level, where children are likely to experience emotions such as anger, upset, or over-excitement, making it challenging to focus and recognize inputs from their surroundings. The “Calm Engine” represents the optimal level where children can focus and listen the best. The “Slow Engine” signifies a state when children are tired, lethargic, or not feeling well.

Similar to the Sensory Ladder, children and adults can combine the chart of the three stages, encouraging children to be aware of their current state using the illustration of the three engine states. Children can then devise their own calming and alerting strategies to manage their arousal level based on the challenges they are facing.

Given that we fluctuate between arousal levels throughout the day, children can maintain a daily logbook tracking their engine state. This logbook serves as a reflection tool for their regulation skills and provides insights into ways to improve.

Practicing self-regulation skills involves a variety of strategies and techniques that individuals can employ to manage their emotions and behaviours. Here are some common practices of self-regulation skills:

The primary objective for adults around children is to observe how they manage their responses in various social situations and to identify and respond to their unique needs in a sensitive manner. Play-based learning experiences have proven effective in helping children practice and establish good social and regulation practices. It is crucial for adults to understand potential stressors in a child’s world and their response (emotional state/behaviour) to challenges. Adults can then assist children in adopting a more mature style of regulation through modelling and guidance.

For example, instead of reprimanding children for being distracted or having difficulty sleeping at night, adults should investigate the underlying reasons and adjust the environment, providing necessary support for optimal outcomes. Once children return to an optimal, calm, and focused arousal level, they are better positioned to attentively listen and reflect on themselves, equipping them with better regulation for future challenges.

Balanced Lifestyle for a Healthy Brain:

With the cognitive demands of self-regulation, maintaining a healthy lifestyle is vital for children’s brain development. Emphasising a balanced use of time across seven categories is essential:

Adequate and quality sleep is crucial for cognitive function, memory consolidation, and overall well-being. Establishing a consistent sleep routine promotes a healthy brain.

Regular physical activity supports not only physical health but also cognitive function. Exercise stimulates the release of neurotransmitters, contributing to improved mood and cognitive abilities.

Allocating time for focused and concentrated activities, such as homework or tasks that require cognitive effort, helps enhance cognitive skills and concentration.

Engaging in introspective activities or self-reflection contributes to emotional intelligence and self-awareness. This time allows children to understand their emotions and responses.

Unstructured downtime is essential for relaxation and stress reduction. Allowing moments of rest and leisure contributes to overall well-being and mental health.

Play is a fundamental aspect of childhood that promotes creativity, problem-solving skills, and social development. Incorporating playtime into a child’s routine fosters a healthy and well-rounded brain.

Building strong social connections is crucial for emotional well-being. Spending quality time with family and friends promotes a sense of belonging and contributes to positive mental health.

Every aspect of life serves as a learning opportunity for children. Adults should value Connecting Time and Playtime as crucial for building trusting, secure relationships and demonstrating good social behaviour through modelling. A healthy sleeping routine is an additional advantage, rejuvenating a child’s brain for a new day.

When Being the First Responder:

Children are more likely to learn and listen when they are calm, secure, and safe. Consider the child’s environment and take actions accordingly. For instance, if a child finds a noisy classroom stressful, it can be beneficial to relocate them to a quieter space, bringing them back to an optimal arousal level for the next class. When a child struggles with regulating emotions, adults can start by validating their feelings, introducing self-regulating behaviours (strategies), and then asking them to make sense of the situation. Providing children with an appropriate level of control and reasonable choices can also help them feel understood and accepted.

Deep Breathing:

Scientific evidence demonstrates that deep breathing is effective for regulation. Children can benefit from practicing abdominal breathing (diaphragmatic breathing), which helps them return to a calm and focused state. Various techniques make breathing easy for children to follow. The lengthier the outbreath, the better it triggers the parasympathetic response, aiding in calming down.

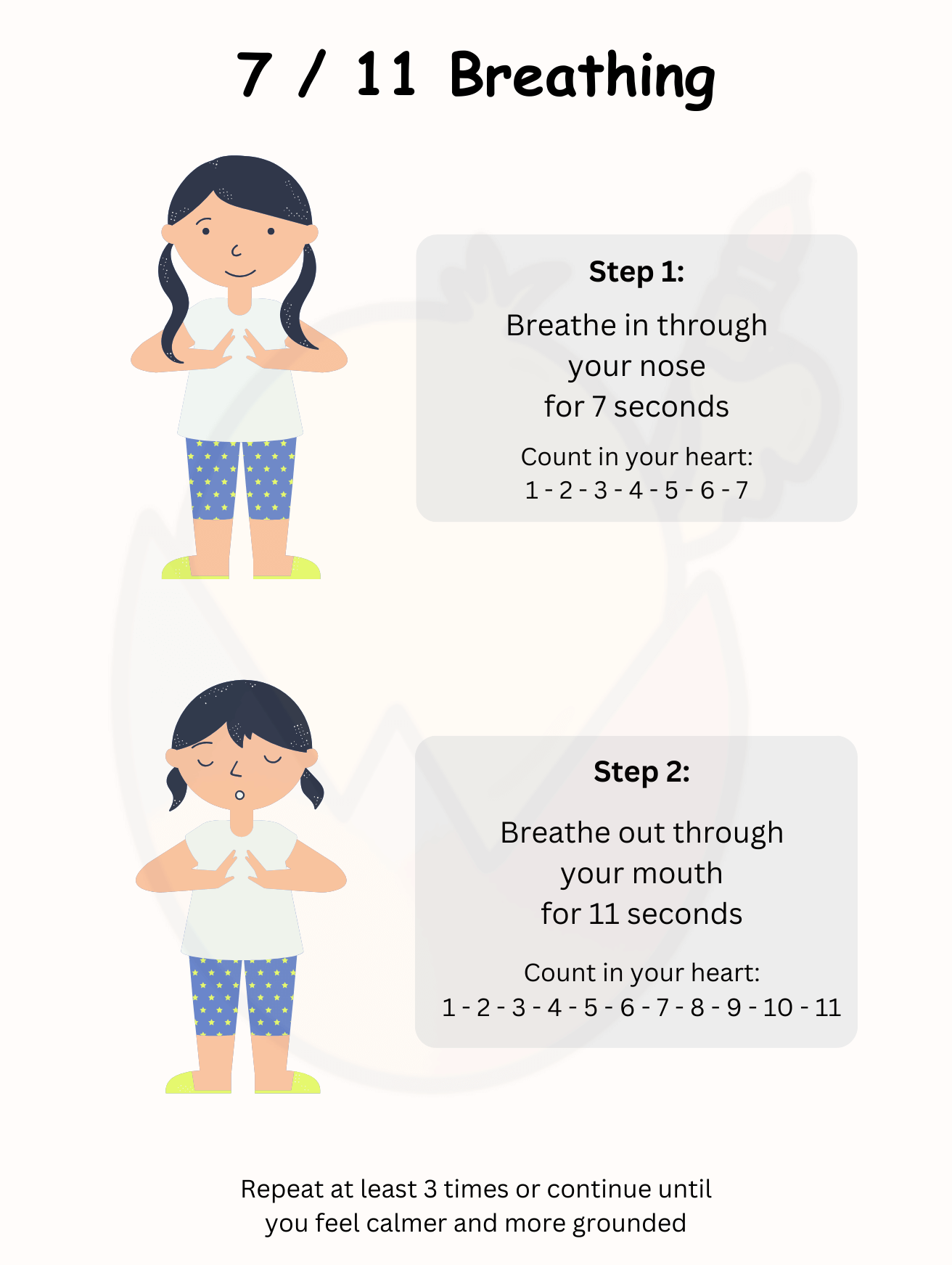

7-11 Breathing:

Inhale for 7 seconds, exhale for 11 seconds. Adjustments can be made for young children with a 3-5 breathing pattern.

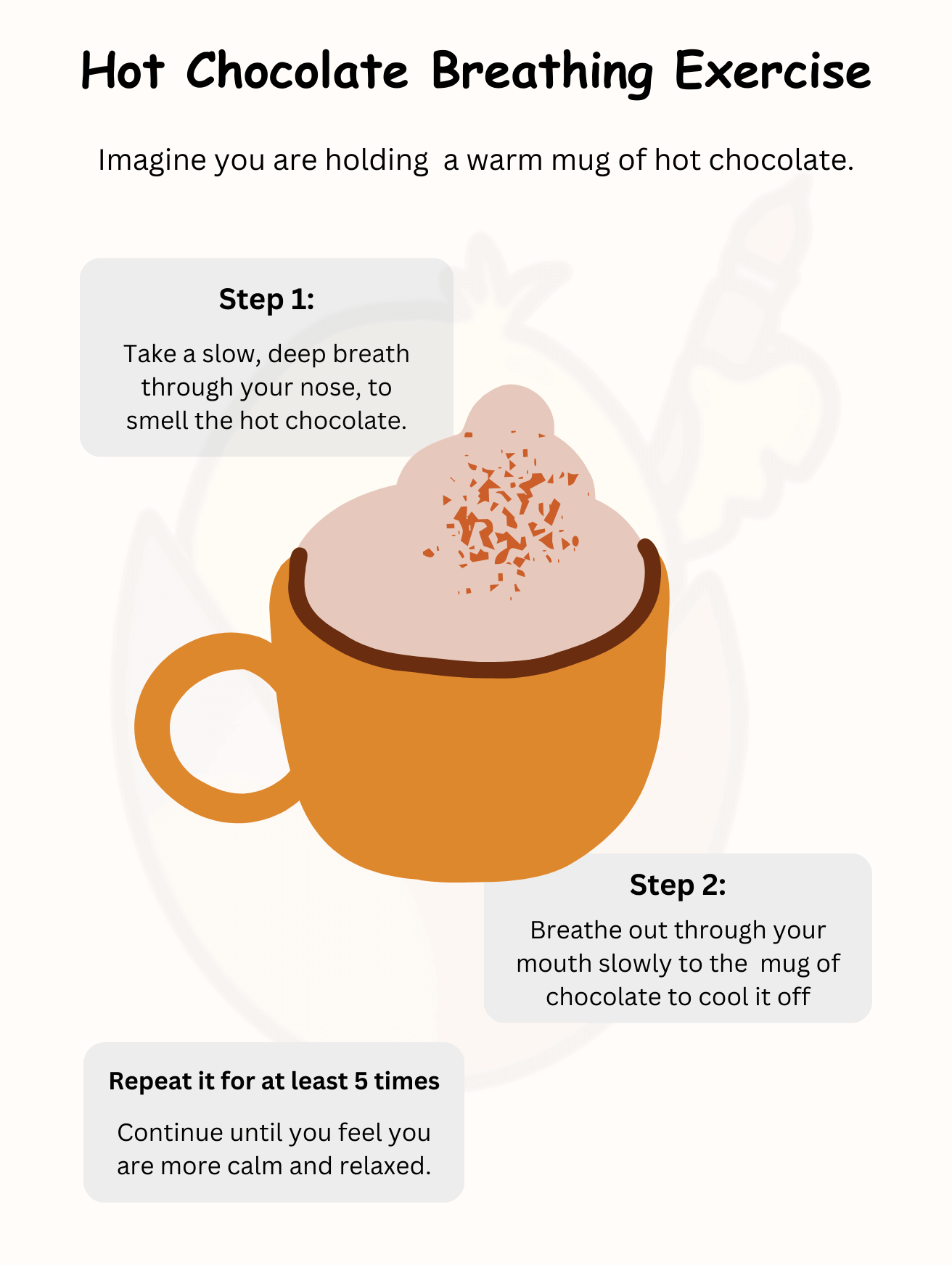

Imaginary Breathing:

Visualizations like blowing bubbles or imagining smelling hot chocolate and gently blowing to cool it down can engage children in the process.

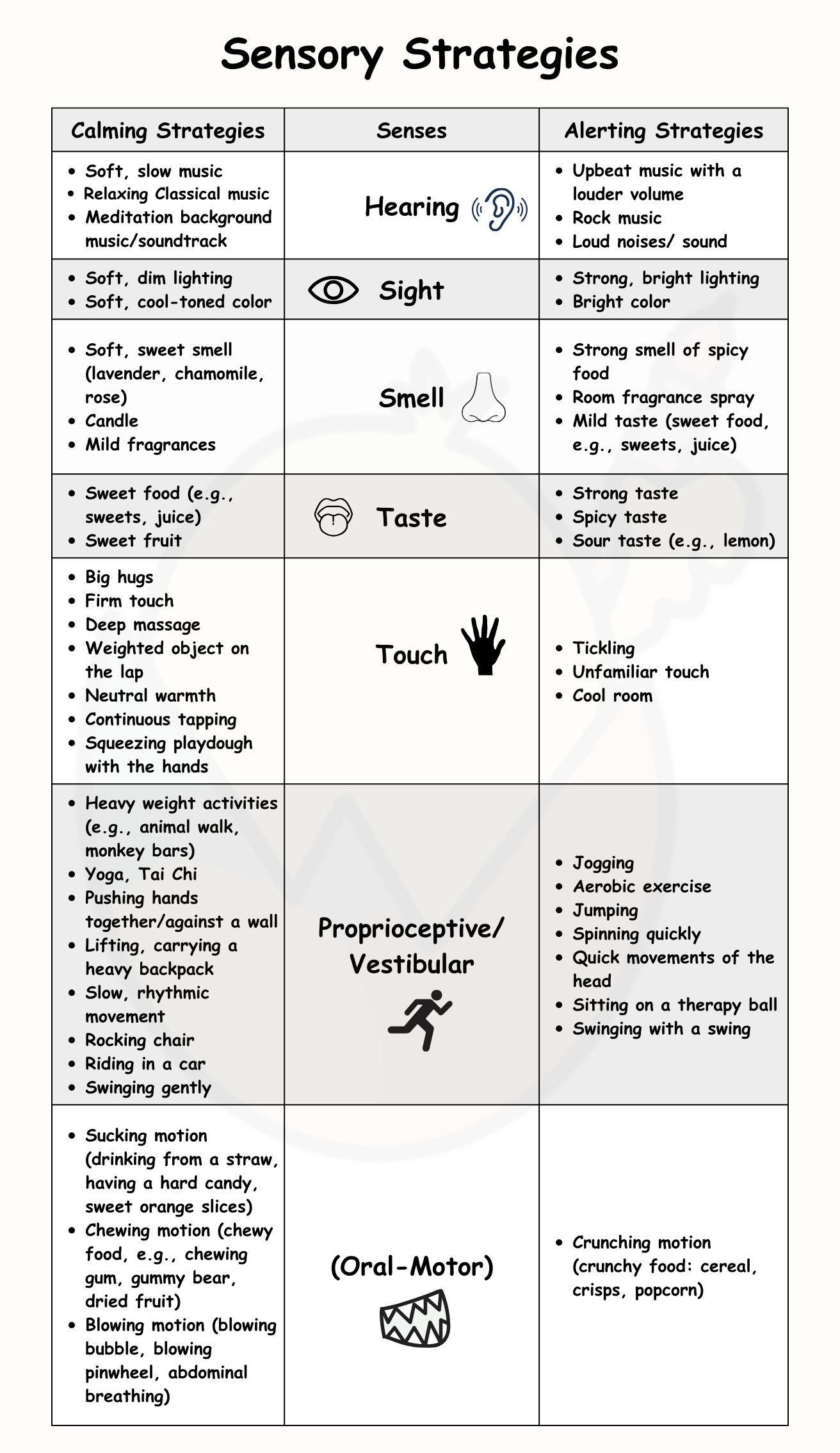

Sensory Strategies:

Several sensory tips can assist in calming or alerting children to an optimal state for improved focus and attention.

Drinking from a straw engages strong proprioceptors in the jaw, providing a soothing effect and helping children return to a calm and organised state, facilitating better listening and thinking.

Physical exercises and activities involving heavy work provide deep pressure and proprioceptive input, aiding the brain in returning to a calm and focused mode. Children can engage in activities such as star jumps, animal walks, or heavy work activities like lifting, pulling, and pushing. Playground activities and yoga ball exercises are also beneficial for self-regulation. Additionally, exercise stimulates the production of chemicals like endorphins, contributing to an improved mood.

These sensory strategies offer practical ways to support children in self-regulation, helping them manage their arousal levels effectively. Incorporating such activities into daily routines can contribute to a more positive and focused learning experience.

These strategies cater to different sensory preferences, offering options for both calming and alerting activities based on the individual’s needs. It is best for adults to try out strategies with children, observe what they prefer, and encourage them to keep these techniques for themselves when they need to regulate.

So here you go! Helping children build up self-regulation skills and develop their own coping strategies when encountering challenges is one of the most crucial tasks for adults. It can be a long journey, but it will be very rewarding once you see them become more resilient and independent in dealing with day-to-day events. If you find helping your child build up self-regulation skills challenging, even after trying the tips from here, it would be great for you to seek professional advice from local experts for a more comprehensive assessment. They can provide guidance according to your child’s strengths and weaknesses and guide you with step-by-step strategies to support your child.

Thank you for reading. Stay tuned for more useful information coming your way. Until then, see you!

ASI Wise. (2024). “Sensory Ladder”. Sensory Ladder for Regulation. https://sensoryproject.org/sensoryladders/.

Australian Children’s Education & Care Quality Authority. (2021). Self-Regulation a foundation for wellbeing and involved learning. https://www.acecqa.gov.au/sites/default/files/2021-01/SelfRegulationAFoundationForWellbeing.PDF.

Barnes, K. J., Vogel, K. A., Beck, A. J., Schoenfeld, H. B., & Owen, S. V. (2008). Self-regulation strategies of children with emotional disturbance. Physical & Occupational Therapy in Pediatrics, 28(4), 369-387.

Government of Jersey. (2020). The Window of Tolerance: Supporting the wellbeing of children and young people. https://www.gov.je/SiteCollectionDocuments/Education/ID%20The%20Window%20of%20Tolerance%2020%2006%2016.pdf.

Hoyer, R. S., Elshafei, H., Hemmerlin, J., Bouet, R., & Bidet‐Caulet, A. (2021). Why are children so distractible? Development of attention and motor control from childhood to adulthood. Child development, 92(4), e716-e737.

Kashman, N., & Mora, J. (2005). The Sensory Connection: An OT and SLP Team Approach-Sensory and Communication Strategies That WORK!. Future Horizons.

Locala. (n.d.). Sensory Ladder Tool. https://www.locala.org.uk/fileadmin/Services/Sensory_OT/Sensory_Ladder_Toolkit.pdf.

Martini, R., Cramm, H., Egan, M., & Sikora, L. (2016). Scoping review of self-regulation: what are occupational therapists talking about?. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 70(6), 7006290010p1-7006290010p15.

Moore, K, A. (2024). The Sensory Connection Program Handbook. https://www.therapro.com/The-Sensory-Connection-Program-Handbook-E-Book-version.html.

NHS University Hospitals Dorset. (2024). Children’s Therapy Services Patient Information Alerting and Calming Strategies. https://www.uhd.nhs.uk/uploads/about/docs/our_publications/patient_information_leaflets/Childrens_therapy/Alerting_and_calming_strategies.pdf.

Paediatric Occupational Therapy Trafford Children’s Therapy Service. (2021). Information. Sensory Pre-Referral Graded Approach. Occupational Therapy Advice. https://traffordlco.org/app/uploads/2021/08/Sensory-Pre-referral-Graded-Approach-003-1.pdf.

Parham, L. D., Clark, G. F., Watling, R., & Schaaf, R. (2019). Occupational therapy interventions for children and youth with challenges in sensory integration and sensory processing: A clinic-based practice case example. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 73(1), 7301395010p1-7301395010p9.

Shanker, S. (n.d.) commissioner for children and young people, Western Australia. https://www.ccyp.wa.gov.au/media/2090/self-regulation-by-dr-stuart-shanker.pdf.

Shanker, S. (2021). Self-regulation: 5 Domains of Self-Reg. Shanker Self-Reg ® resources. https://self-reg.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/infosheet_5-Domains-of-Self-Reg.pdf.

Williams, M. S., & Shellenberger, S. (1996). How does your engine run?: A leader’s guide to the alert program for self-regulation. TherapyWorks, Inc.